- Home

- Steven Price

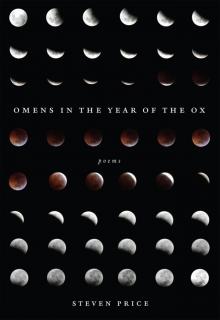

Omens in the Year of the Ox

Omens in the Year of the Ox Read online

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Price, Steven, 1976-

Omens in the year of the ox / Steven Price.

Poems.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-771314-03-9

I. Title.

PS8631.R524O64 2012 C811'6 C2011-908120-2

copyright © Steven Price, 2012

We acknowledge the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, and the Ontario Arts Council for their support of our publishing program.

Cover design by Michel Vrana.

The author photo was taken by Esi Edugyan.

The print edition of the book is set in Bembo.

Brick Books

431 Boler Road, Box 20081

London, Ontario N6K 4G6

www.brickbooks.ca

About this Book

Omens, curses, the reading of entrails: means of grappling with what is out of our hands, beyond our ken.

Steven Price’s second collection is part of a long-lived struggle to address the mysteries that both surround and inhabit us. The book draws together moments both contemporary and historical, ranging from Herodotus to Augustine of Hippo, from a North American childhood to Greek mythology; indeed, the collection is threaded with interjections from a Greek-style chorus of clever-minded, mischievous beings—half-ghost, half-muse—whose commentaries tormentingly egg the writer on. In poems that range from free verse to prose to formal constructions, Price addresses the moral lack in the human heart and the labour of living with such a heart. Yet the Hopkins-like, sonorous beauty of the language reveals “grace and the idea of grace everywhere, in spite of what we do.” The pleasures of Price’s musicality permeate confrontation with even the darkest of human moments; the poems thus surreptitiously remind us that to confront our own darkness is one of the divine acts of which humans are capable.

For Jacqueline, old friend

Contents

The Crossing

I

Field Guide to the Sanctuary

Odysseus and the Sirens

Chorus

Jarred Pears under Dust

Icarus in the Tower

The Wrecking

Chorus

Danube Relic

Auto-da-Fé

Bull Kelp

Arbutus

A Gloss on Arbutus

Raccoon in Ditch

Chorus

Reparations

Bach’s Soprano

Orpheus Ascending

II

The Tunnel

Midwife’s Curses

The Tyrant’s Physician

Medea

Ghosts

Gardener’s Curses

Three Blues

The Inferno

Curses of the Blind

Omens at the Edge

III

The Excursion

Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife

Omens in the Year of the Ox

The Persian General

Chorus

Dr Johnson’s Table Talk

Plumb

Odds Were

Kid

The Boy Next Door

Chorus

Late Rehearsal: Requiem in D Minor

The Second Magi Returns to Parthia

Stations of the Geode

At the Edge of the Visible

Transparencies

Mediterranean Light

Omens at Dusk in the Year of the Dragon

Notes & Acknowledgements

Biographical Note

We pass these things on,

probably, because we are what we can imagine.

Robert Hass

The Crossing

I

So. At the end of the middle of your life

you wake, rain-shivering, to a white railing

in a shriven dusk. A strangeness churning

under the hull, the great blades boiling through

ferruginous waters. So the ferries sail still

in this late age, vast holds half-full of souls.

And so you rise, each day, more than you were.

Exhausted, maybe, into silence. When Bridges

wrote, How is the world’s bright shift held

in such a cluttered line? Hopkins, in a rage,

had no answer. Or none beyond his poetry.

Rain in silver ropes overrunning his faith,

his metre marking long great gulps of night air.

So the waters gulp at the mournful hull,

so the rusted bolts bleed. You unfold both

fists in the charred coastal dusk, watching

a white chill krill across their skin. Bright shift,

cluttered line. If the ill of the world issues

up out of the world, then there is no course

but to praise it. As Hopkins praised it. In the straits

a slack foam froths blackly in the scum, and you

who are water stare at that water, blurred

by old hurts praise holds no part in, here

at the edge of a dark crossing that is always

evening. As if called to account for a life

lived in the provinces. But there is no

calling to account. You sway at a railing

staring west, towards desolation, that is, forgetting.

II

In Gaudí’s Palau Güell, with her. How the walls

wept into form, as you wandered hall to hall

in that black building, astonished such a shape

could hold. The built thing made bright shift of.

Gaudí had given Güell an allegory of the cross,

both sculpture and story. It was a spatial truth

he’d sought: an ascension up, up

seven stories towards the spires of heaven.

That cellar with its termitic columns,

that cellar where partisans were tortured,

that cellar of sand, dust, stone: that was Hell.

You rested under the white shards of pottery

on Gaudí’s rooftop, watching a white cat pour

past her ankles like blood-threaded milk

while a red sun drenched the staggered chimneys.

How she looked at you, suddenly perplexed.

And when you asked, What is it? she laughed,

having just forgotten what it was. Nothing,

she said, meaning everything she already had.

There is your desire, and her desire, and each

touches many things. You carried Hopkins

all through Spain, wanting to get closer

to something. His stark Jesuit suffering, perhaps.

Tracing your burned fingers along the cool

ancient stones in the narrow streets

of the Gothic Quarter, his music

in your head. We believe we are living

one life and learn too late we have been

living another, she said. If all our pasts

are possible pasts then we are no kind of gone.

On Gaudí’s tiled roof she pointed past a line

of smoky blue spires in the Barcelona haze,

and you felt your future darken before you.

Does it matter now if none of that is true?

You know that you cannot, maybe, bring her

into that city, where she was not. Still, there

she waits, as you waited, under the locked

iron grillwork of the Palau Güell, sick

with absence, which was the real crossing,

and was in everything, and is, and has no end.

III

The smoky waters are the still sou

r yellow

of poisoned milk. A brooding sky recedes.

At the stern a ragged passenger perches,

collar rolled cold against a windblown dawn,

almost her. You shade your eyes, look away.

Frenzied light, sea like crumpled foil—

the world burns redly up out of the strait,

silent, and vague, and sinister, like a dream

interrupted. You had been reading about love

and evil, how the one would transcend

death and the other deny it. Death

being both bright shift and the upwelling.

So your shadow ducks the deck’s edge

to shatter in the spray, and so you go

back, going back. To the monster that stalked her

through a clattering train carriage in Catalonia,

who shuffled like an old man, who shouldered

no luggage, blue eyes half-kind as he stared

her into meat, trembling with age and what

already had been done and what he would

do again. Evil is its own element,

and real, it pours from itself like a sea, all flux,

whole and divisionless and without center.

When next you see her she will not, it’s true,

be who she was. You watch night bell murkily,

fathoms down, sinking deeper; at the far rail

a faint sun flares, its vicious hooks flowing

round you and in you, clutching for purchase.

In the swells the grizzled gulls glide and cry.

She will never, will never, will never die.

IV

What is steadfast? Nothing is steadfast. You

sailed for the desired world, remembering.

How Gaudí’s friend and patron, Güell, died

of a burst heart in 1918, and the works fell still.

Fierce, shabby Gaudí. Shuffling into decay.

That was the year Bridges dredged up his dead

friend Hopkins’ forced and gnarled verses,

in a brief embarrassed print run. Few copies

survive; the poems go on. What is steadfast?

Sunlight shivers on the face

of the imperceptible now, as if in answer.

V

In the end all is a river that flows from fog

to fog, that darkens the selves within us.

In the end, for the tides, this world is the world

it was. So the waters recede and recede,

so you trudge out after them, hopeless.

Trusting a far shore exists. Absolute

love, wrote Bridges from the long drift

of his fame, is measured hour by hour.

Where I say hours I mean years, mean life,

wrote Hopkins. All of us arrive, somehow,

in the here. The black firs loom and pass

in the cold light of the crossing. Far out,

gulls drift and disarticulate in the grey,

their song an ugly, rasping appetite.

As it is in all of us. The final waters,

fanged and liquid, open under our feet.

Who wrote that? A Spanish poet, most likely.

You remember walking the fragrant lanes

of Mojácar at dusk, the lemon trees belling

low over the orchard walls. As you crossed

a corner into a gulch a huge darkness

detached itself from the ditch and glided

growling out, all sinew and razored shadow

blocking the middle of the end of that road.

Its black hackles bristling. And you understood:

you could go no further.

Field Guide to the Sanctuary

I

A grey lagoon searing dark

with chill winds. Rockstrewn

strands lashed and scoured.

What eddies here wants

no mercy. Is salt and savage.

Snub-blunt and sculling

the grey gulls punch

their weight in the spray, lift,

hang over humped middens

shingled to chalk-shell,

shaled and cold. Watch

their world wheel under.

II

I have seen this, seen

this. The dart and snaking

barb of swans at feed.

A slow child swarmed

by slithers of char-geese, dragged

howling into black water.

The folded plunging incision

of hawks in the wash;

feathers scalpelling the air,

sharpening. Look dead

in any eye: terror

clockworks there.

III

A mallard’s worm-

swaying skull swivots, stabs,

plicks at greased gun-

feathers underwing. A wind rises:

the steel waters sheen and chop.

One gull swells up, is blown

like a plastic bag out over the drop;

most wait out the worst

huddled grim. The world

here is harsh, guttural, or still.

Threnody plays no part.

On an outcrop, now, kneel,

observe the birds’ ferocious art.

Odysseus and the Sirens

Here

their

fear

churned

him hard;

that scarred

smoke-glarred

strand burned

like black shell;

his men held

their ears well-

stogged with wax

and cut, dipped, dragged

through froth oarblades,

old shafts gone grey—

their knuckled backs

wracked by hard rowing—

as, lashed fast, flowing

with rope and roping

his muscles in knots

of their own cording, he,

Odysseus, hung; leaned

low, gasping at that beam,

bloodied ears shunted shut—

when came the breached dream out of the sea.

Scorched wharves. Slit fish noonspackled with heat.

Now was this land that he knew; now surging on past could he make out

white hills, sunhammered, walls hazed in the blur

and his eyes afire hawked fast, hunted her—

not this, nothingness, this

no-song of wind and hiss

and spray, gulls in tall gusts

shoaling over shore rocks—

in that rain-flared chop

their oars, all surge and scup

of salt-stripped cedar, stopped;

he stared back in shock:

a battered beach,

kelp-strangled, seethed

with mysteries

and wind-amped cries

damp with want;

he shook then;

he, ropes rent,

shut his eyes—

that land

of stunned

black sand

was love:

shore

our

horrors

sing of.

Chorus

In they’d drift, almost motes, like echoes

of the eye, like articles of dust

stirred in the drapes’ dreary pall.

“See with the eye,” they admonished,

“and seeming will be less and less.”

“He has no ear for longing,”

sighed one, or was it: “He hears no air

of longing”? I screeled clear the drapes

on tarnished rods, seeing neither shape

nor shroud. “See,” said another,

“he sees nothing not his own.”

“We are his own.” “Or were his own.”

Knuckling shut my eyes to caulk shut

my skull. “He thinks he can ignore us,”

; one hissed; “this singing he signed on for

never had sense in it.” “Stubborn.”

For God’s sake, I muttered, I can hear you,

I’m here, I’m right here—

At which each silvered into blessed silence.

I listened to the sweet nothing

adrift in the drapes. But then:

“Did he just say he’s right?” “Right here.”

“Who is he?” “What is right?”

“Where is here?”

Jarred Pears under Dust

A man’s bruised hand glows

like glass. Unthreads the lid,

pries back the brass cap

in a wet suck of icy air.

Jarred pears drift in flecks

of what serene fire, drift

burning with what sweetness.

In any jar an inner autumn

rises: calved pears float

pure, float white; and a boy’s

bruised hand pours out

light. We walk a heavy

orchard all our days

to watch such white fruit fade.

Icarus in the Tower

As if winched in harness

he works late, his withered desk’s

worn olive-wood blurred—

works, all wax and bristling

quill in the murky wine-dark shine.

O my strange, sad father.

How he does not see me.

Tangled in the bars of our cell

the lyred tendons

of dried seabirds

stretch, or split, or dangle

over scrolls we sketched for lift.

I lie like a coal in the dark straw

seething with light.

I stare and stare.

He shuffles forth

in his frail creaking contraption

of leather-twined harness,

rib-crossed strap. In candlefire,

clips the brass buckles fast,

the wings soft in the smoky burn.

Then turns; mutters; widens

the twiggy light-as-bone

wingspan of his wattled arms.

By Gaslight

By Gaslight Into That Darkness

Into That Darkness Omens in the Year of the Ox

Omens in the Year of the Ox